Rumor and hysteria fueled the fires of tragedy as the veneer of civilization fell away from ordinarily quiet, law-abiding men on a day they and their descendants remember with shame and regret.

Attempts were made to prosecute those responsible for the lynching, and eventually about a dozen men were indicted. The victim had been shot many times, but the evidence was conflicting, and many people were involved.

The judge, presiding over his courtroom in the Hendry County Courthouse, declared it was impossible to fix blame on any particular persons. Consequently there were no convictions; and the case was dismissed.

After the lynching, the spring weather was hot and dry. There had been little rain, and farmers were anxiously watching the sky. Eventually clouds began to form, and a welcome rain was anticipated. As the clouds built up, the sun was blotted out. Thunder boomed and rumbled in the distance, but when the rain came, it was only a few spattering drops, barely enough to dampen the dust in the unpaved streets.

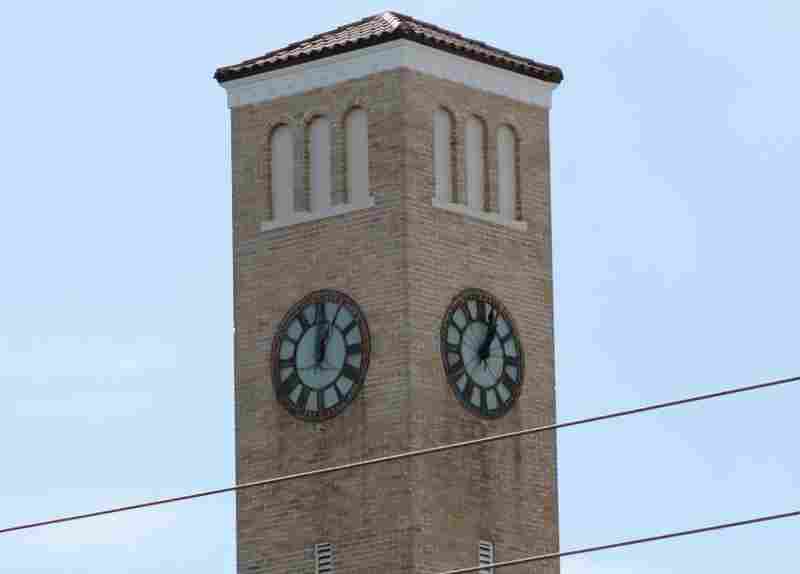

Suddenly, a shattering crash seemed to shake the earth, followed by the strange tolling of a bell. Lightning had struck the courthouse clock tower, smashing and burning the clock works and motor. The vibrations of the bell seemed to linger as the storm swiftly passed and the clouds rolled away.

It was an accident of nature, of course, and the county commissioners quickly repaired the clock. Then it happened again – and again. The wiring was re-inspected, lightning rods were installed on the tower and the tiled courthouse roof. Every conceivable precaution was taken, but nothing seemed to do any good. Repeatedly the clock was repaired, and each time, lightning smashed again into the tower.

The story began to circulate that the repeated lightning strikes on the courthouse weren’t really accidents of nature, but a sign of God’s anger against the town. “Bosh,” snorted the commissioners, and repaired the clock. However, after each repair, lightning struck again.

Then on July 4, 1929, as citizens prepared to observe the holiday, there came a bolt so vicious and terrifying that everyone in town was stunned. People rushed into the courthouse and stood aghast. The lightning had smashed a large section of cornice stone from the top of the tower.

The huge stone had crashed through the roof and buried itself in the floor, almost on top of the judge’s bench in the courtroom where the abortive trial had been held. This time, there was no ignoring the charge of “divine retribution.”

LaBelle clock tower today, LaBelle, Florida

Newspapers across the state picked up the story and pointed fingers at LaBelle, and the legend spread that time would stand still and the town would live with the symbol of its guilt until God’s wrath was appeased.

In desperation, the commissioners had the clock dismantled and its works stored in the courthouse basement. They removed the hands from the clock, and its four faces remained, mute and useless, a landmark visible from every direction. But now many averted their eyes, for its presence was a grim and constant reminder of the events of that terrible day.

Years passed and changes took place. The town grew and new people arrived. Old people died, babies were born, and life went on. People didn’t want to be reminded of the lynching and didn’t talk about it and newcomers had never heard of it.

The townspeople became so accustomed to seeing the courthouse clock without hands that some began to assume there had never been any. At least one book was published with a photograph of the courthouse and annotation that things were so easygoing in LaBelle, that “the clock did not bother to keep time.”

Perhaps God was being appeased, and perhaps it even helped when the old bell was removed from the clock tower and donated to the new First Baptist Church. In fact, that may have been the turning point, for after the bell was hung in the church steeple, lightning never again struck the clock tower.

There is nothing like being sure, though, and folks in LaBelle had grown cautious over the years. Besides, no one really wanted to be the first to test the wrath of God. As years passed it was finally decided that new works would be installed in the clock tower as well as new hands on the four faces.

Newcomers watched curiously, and old-timers literally held their breath as the switch was thrown and the gears began turning on the courthouse clock on Saturday, February 22, 1975, at 3 p.m. Time had started again in LaBelle.

Reprinted from Gulf Shore Life, February 1984